Too many individual designs, too little common ground: Fincantieri boss Pierroberto Folgiero is calling for more standardization in European naval shipbuilding. But between large state-owned corporations, family-run shipyards and fragmented supplier structures, it becomes clear why technical rationality alone will not overcome European fragmentation.

In an interview in the Financial Times, the CEO of the Italian shipyard group Pierroberto Folgiero has revived a debate that has been smouldering for years. According to his diagnosis, Europe has too many individual national designs in naval shipbuilding. Common specifications, reusable platforms and modular design approaches are necessary in order to shorten development times, limit costs and remain competitive with Asian series shipyards. What initially sounds like an industrial-economic demand actually touches on a core conflict in terms of security and industrial policy.

Standardization as a prerequisite for the ability to act

Folgiero explicitly links his criticism to the growing strategic importance of maritime underwater warfare. In view of vulnerable submarine cables, increasing Russian activity and rising requirements for submarine hunting and the protection of critical infrastructure, Europe can hardly afford a small-scale fleet policy with lots of one-offs. Although Fincantieri does not build any submarines itself, the Group is positioning itself as an integrator and orchestrator of this area of capability. Submarine-hunting-capable surface vessels, unmanned underwater vehicles and sensor technology should not be thought of as isolated individual solutions, but rather as coordinated building blocks within compatible platform and architecture approaches.

In this understanding, standardization is aimed less at short-term efficiency gains and more at increasing the military’s ability to act. Standardized platforms and interfaces shorten integration and modernization cycles, facilitate the scaling of capabilities across multiple units and improve interoperability within the alliance. The ability to act is thus not created by individual technical peaks, but by available, interchangeable and sustainable maritime forces.

European cooperation projects between aspiration and reality

European cooperation projects in recent years show how these demands can be implemented in practice. One testing ground is Naviris, the joint venture between Fincantieri and the French Naval Group. Programmes such as the Horizon upgrade and in particular the European Patrol Corvette (EPC) aim to establish a common basic design for so-called second-rank warships: standardized hulls with national mission modules, coordinated via OCCAR and co-financed by the European Defence Fund. These programmes are not part of Folgiero’s interview, but are often used as practical references for the standardization he calls for.

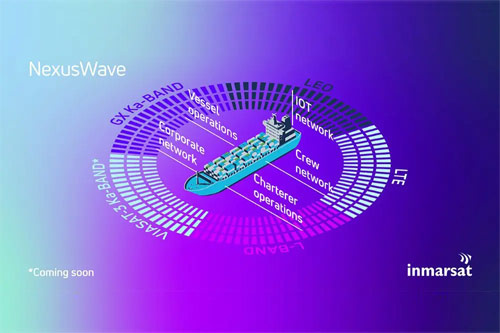

In addition, digital initiatives such as EDINAF, led by Navantia, are driving forward the harmonization of software architectures. The aim is to create a common digital starting point for future surface and underwater units – an approach that transfers standardization from the platform to the system and integration level.

At the same time, standardization remains highly sensitive in terms of industrial policy. France continues to rely on the Naval Group as a national champion with an end-to-end product range, while Germany initially wants to create industrial mass by consolidating its shipyard structure – a step that can facilitate standardization, but not replace it. Other players such as the Damen Group have been pursuing modular series approaches for years, but warn against a standardization that leads to proprietary ecosystems of a few large corporations.

Standardization and consolidation – two different debates

In the debate, standardization and consolidation are often equated. In fact, they are different processes: While standardization concerns technical baselines, interfaces and platform logics, consolidation targets ownership, market and power structures. Both intertwine, but are politically and industrially conflict-prone in different ways.

The benefits of technical standardization are undisputed. However, its implementation fails less because of engineering issues than because of Europe’s industrial reality. The European naval shipbuilding ecosystem is deeply divided along ownership forms, business models and supplier structures: state-owned large corporations such as Naval Group, Fincantieri and Navantia are pitted against family-run, export-oriented shipyards such as the NVL Group or the Damen Group.

In addition, there are different organizational forms in the supply chains: While in countries such as the Netherlands, shipyards, design expertise and suppliers are more strongly bundled along modular series and export logics, the maritime supply landscape in Germany is technologically capable, but historically broader-based and more project-oriented. A high level of technological depth is offset by a lower level of overarching standardization and coordination.

In this environment, standardization does not automatically mean efficiency, but touches on issues of control, value creation and industrial role. Living it therefore requires much more than technical unity: political control, industrial policy balancing mechanisms and the willingness to abandon national special paths in favor of common architectures would be necessary. By Hans-Uwe Mergener